Math Arguments

Problems, Questions, and Puzzles to spark discussion and argument in the maths classroom.

Order of Operations is Wrong

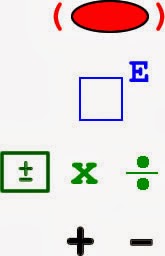

I've always liked the version to the right as it displays the order of operations in a hierarchical fashion, which helps to eliminate a lot of the issues that students have.

They memorized PEMDAS and assume that M comes before D, such that

\(30 \div 6 * 5 = 1\)

when the intent was for

\(30 \div 6\), then \(5*5\).

Here's another: \(10^2 - 5^2 \div 5\)

The order of operations is most appropriately a way to ensure that everyone can communicate in a consistent fashion, that there isn't really a "natural reason" as much as there was a human one. "It's just an arbitrary rule" was one of the most-viewed posts on MathCurmudgeon, relating the story of an expression that only 30% of over 300,000 Facebook users got right. (And because Facebook is what it is, they were all certain that they were correct.)

\(6-1*0+2 \div 2\)

... but here is an interesting viewpoint. What is your take on it?

Transcript

If you went to elementary school in the United States (or much of the rest of the world) you almost certainly learned about something boringly called the "order of operations" - a set of rules for whether or not you should do multiplication before addition or addition before subtraction to get the right answer on your math test.

Except, you don't always get the right answer, or even, one answer - I mean, is 8-2+1 equal to 5 or 7? and is 6/3/3 equal to two thirds or six? - the problem is, focusing on the order of operations can lead to ambiguity and obscures the real, underlying, and often beautiful mathematics.

A mathematician will tell you that 8-2+1 is really 8+(-2)+1, which is unambiguously equal to 7, even though the so-called "order of operations" standard in the US tells you the answer is 5. If you want five for your answer, then you really need some parentheses! But why is this ambiguity even possible? Because fundamentally, all of these operations are simply different procedures that start with two numbers and combine them in some way to give you a single number. Each operation takes two numbers as input - two, and no more. If you want to be entirely unambiguous (and pedantic), every single pair of numbers in an algebraic expression should be inside parentheses, and then there's no need to know ANY order of operations - just evaluate the innermost parentheses first, and work outwards, collapsing them down pairwise like a championships bracket.

But it turns out that's not the only way - it's possible to CHANGE the order in which you do the operations, to rearrange the parentheses, as long as you know what the underlying mathematics IS. For example, if you want to add (3+4) and then multiply the result by 5, you can either do the addition first and get 7 times 5 = 35, or you can do the multiplication first as long as you know that multiplication "distributes" across all the terms in the parentheses... that is, (5*3) plus (5*4) = 15 plus 20 = 35 - the same answer! And how do we know multiplication distributes? One way is to draw rectangles ... but I've done that before.

The same rearranging can be done for exponentiation and multiplication: (3*2) all squared (or 6^2=36) is the same as 3 squared times 2 squared - 36; It even works for addition and subtraction: 5 minus (1+2) is (5 minus 1) minus 2.

So, the true order of operations is this: use parentheses, and learn what exponentiation, multiplication, addition and the rest are REALLY doing - then you can proceed however you want.

That's not to say that we don't have a conventional order of operations in mathematics... I mean, deciding that we evaluate multiplication before addition allows us to get rid of lots and lots of redundant parentheses, and noticing that (1+2)+3 = 1+ (2+3) and 2*(3*4)=(2*3)*4 removes a ton more... but the point is that those parentheses are still there, still implied - just like how 3 minus 4 is secretly implying 3+ negative 4 and 3 divided by 4 is really 3 times one fourth. But any time the result might be ambiguous, you really need to use parentheses. Then you can proceed in whatever order you want.

The order of operations learned in school, however, is different - it's a mechanical set of instructions that dictates just one of many ways you can do algebra - it locks you into a single path through the beautiful mathematical landscape, which, while necessary for a computer whose goal is merely to give you the right answer, doesn't really give any insight onto WHAT IT IS that you're doing

when you do algebra.

So, while, the order of operations isn't technically wrong, because most of the time it'll give you the right answer, it's morally wrong, because it turns humans into robots.

.

++

++